by Nicholas Haggerty

語言:

English /// 中文

Photo Credit: Alfredoko/WikiCommons/CC

On July 1, 2003, about 500,000 people marched in Hong Kong in opposition to an anti-subversion statute, Article 23 of the Basic Law. Until this past June, when two million took to the streets of Hong Kong, the protest was the largest political demonstration in post-handover Hong Kong.

I asked Cardinal Joseph Zen, then recently appointed bishop of Hong Kong in 2002, about his precise role in the protest that year—he has been widely cited as its most vocal spokesman by scholars of religion in China and Hong Kong. He briefly discussed the main reasons for his opposition (Beijing’s ability to declare the church a treasonous organization) and his tactics (strategic alliance with Falun Gong in opposition) but did not want to dwell on the apparent peak of his political and popular influence in Hong Kong. After leading several thousand faithful in prayer at Victoria Park before the main march, he left the scene to spend the day in prayer. He was more concerned with the protests happening now, and with his battles within the Vatican bureaucracy.

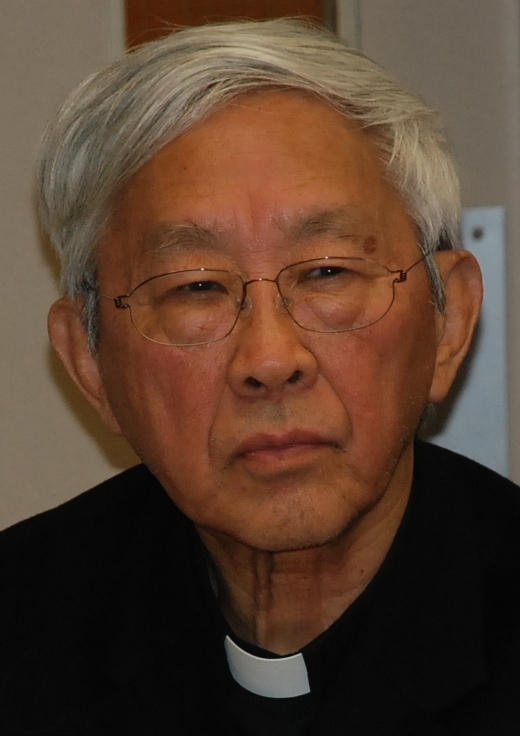

Cardinal Joseph Zen. Photo credit: Jindřich Nosek (NoJin)/WikiCommons/CC

Our interview took place the morning after the mass at the Salesian House of Studies, on Hong Kong Island. An officious Salesian brother met me at the door and invited me to breakfast in the refectory. Faded framed photographs of Pope Benedict and Cardinal Zen were hung side by side above the entrance—images of the current leader of the diocese Cardinal John Hong Ton and Pope Francis were on the opposite wall facing the entrance. Cardinal Zen came to meet me a few minutes later, and as I finished, he began by speaking of the current situation in Hong Kong.

Zen has noticed the difference in attitudes in the current protest movement between students and older generations, who unsurprisingly urge moderation and not the more aggressive tactics of the students. (It must be said as well that our interview took place in mid-September, before further police escalations, including the use of live ammunition and the siege of PolyU). As for where Zen himself stands in the generational divide, Zen himself has shown solidarity and admiration for their courage beside remonstrations on the importance of reflection on the similar mistakes of past social movements in Hong Kong.

Zen told me the Hong Kong government, and the central government in Beijing are cunning—so the students need to match them. He stressed that “It’s time for the older generation to unite with the younger.” He marched in the largest rallies of June, but since then has participated in a supporting role, as one of five trustees responsible for a large humanitarian fund of assistance to those wounded, arrested by police, prosecuted and also to the families affected. In his capacity as an official chaplain he frequently visits prison and continues to write on his personal blog.

At this point, I asked Cardinal Zen about the story of his involvement with the Vatican on China issues. In September 2018, a secret accord was reached between the Vatican and China.

I reproduce in full, edited for clarity’s sake, this section of our conversation below.

Nicholas Haggerty: You were born in Shanghai. Were your parents Catholic?

Cardinal Joseph Zen: Yeah. They were first-generation Catholics; I was the second generation. I left Shanghai in 1948, I was 16 years old.

NH: Where did you go? Did you go right to Hong Kong when you were 16?

CZ: I came here to join the Salesians. This house.

NH: Would you define yourself as Chinese?

CZ: Sure. So when they discuss about the independence of Hong Kong, I said “No. What do you mean?” They say, “We don’t want to be mixed with China” We don’t care about China, we want Hong Kong—” I said “No, I care for China. China belongs also to me. I want it back from the hands of the Communists. I will never be satisfied only to be a citizen of Hong Kong. No, no, I am Chinese.

NH: What battle is taking up more of your time now? Are you more concerned about developments in the church—with Pope Francis and the secret deal with Beijing—or are you more occupied with Hong Kong right now?

CZ: Much more with China. The whole church in China—terrible, terrible. Terrible. Terrible.

Unfortunately, my experience of my contact with the Vatican is simply disastrous.

I was made a bishop by John Paul II. But actually it was not his decision. It was the decision of his collaborator, Cardinal Tomko—the head of the Congregation for Evangelization at that time.

Cardinal Zen in 2014. Photo credit: VOA/Public Domain

Cardinal Zen in 2014. Photo credit: VOA/Public Domain

Why? Because at that time, fifteen years before 2000, in China you had a new open policy. Cardinal Tomko wanted to be involved, and he comes from Czechoslovakia. He knows the Communists. He has long experience in the Vatican. He was a good friend of John Paul II. He managed to work very well.

There was no commission on China at the time, but he began by calling secret meetings. These meetings had sessions every year, or sometimes two years. Tomko said to me, “Join the meetings. Join the meetings with the Vatican Secretary of State and Congregation for Evangelization—the two departments which care for the Church in China.” Enlarged meetings—also invite someone from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Two or three experts, some bishops, a few people. Five or six people from here.

These secret meetings were very useful because Tomko could gather much information. China was open. Many people visited China, they brought messages. We could examine the situation, give advice, even made some unofficial contact with the government.

Tomko was a very balanced man. He started from a hard line to defend the Church from persecution. But when we brought the news that in China, even in the so-called official Church, there are many good people that just happen to be there in that church.

So Tomko started a very open policy. He started from a hard line but he was open to reason. And so it went very well all those years.

Well, as much as possible.

It was necessary to have some compromise, but still, fundamentally to say the right position of the Church.

The Holy See legitimized several illegitimate bishops. Why? Because they were good people. They were under very hard pressure. And the government did not dare to choose the worst persons. So these were good people—maybe timid, so they accepted to be ordained illegitimately. But then they asked for a pardon, promised to do well, so the Pope legitimized them.

And then there were young people, priests, the government chose to be bishops. Again, they are good people, may not necessarily be the best ones. And they are also courageous enough to ask for permission from the Pope. They said, “Without permission from the pope, we would not accept to be ordained.”

Very courageous. After some investigation, they were approved.

NH: What changed?

CZ: Unfortunately, in the Church there’s a law regarding an age limit. So at 75, Tomko had to retire. Then the successor was no good. And the successor of the successor, even worse.

What I mean is that there is a group in the Holy See. These people have power there. They used to be legitimately in power because all the people enjoyed the trust of the Pope. But then under John Paul II, the direction is already different. But because of the Pope and Cardinal Tomko, these other people had no real power—for awhile. But when Tomko retired, and Crescenzio Sepe was appointed—Sepe was no good. These were the people who had the power. So the Congregation for Evangelization did almost nothing. They just carried on the strategy of Tomko, but not really in that spirit.

Just imagine: in the year 2000, there was a planned ordination of 12 bishops in Beijing, on the same day as the pope was ordaining twelve bishops in Rome. Actually, it was a failure. Only five showed up. Others refused to be ordained. Anyway, that was a clear act of defiance. And this new prefect legitimized almost all of these five very quickly. Incredible, incredible.

After Sepe came Ivan Dias. Pope Benedict appointed Dias. Now, everybody thought it was a wonderful choice, because Dias is an Indian who worked a long time in the Secretary of State. He was nuncio in two or three countries, and at that time he was archbishop of Bombay, the biggest diocese. So to call him to the Vatican may be the first Asian Prefect of a Congregation then, so it’s a very good thing.

But unfortunately, Dias was a disciple of Agostino Casaroli [Editor’s Note: A Vatican official famous for Cold War-era diplomacy with the Eastern Bloc]. So he believes in Ostpolitik. Both Pope Benedict and Tarciscio Bertone were considered as outsiders. They don’t belong to the group. Even though Bertone is Italian.

In the Secretary of State, those who had the real power were not the highest officials, but those down below them. Especially in dealing with China.

Pietro Parolin at the time was the under-secretary. That means the chief negotiator. There was not a commission, but only a member of the secretary of state, actually the undersecretary, who went to have some unofficial contact with China, he reported, he briefed the secret meetings on everything. We could give our advice, etc.

Photo credit: Rock Li/WikiCommons/CC

Photo credit: Rock Li/WikiCommons/CC

Now under Pope Benedict, he did two very important things. One is to write a letter to the Church on mainland China twelve years ago. A wonderful letter. But can you imagine that the Congregation for Evangelization under Dias; they manipulated the Chinese translation?!

And then the Pope also set up a commission. Now, between Dias and Parolin, they just made that commission to not work at all. First, they manipulated the working of the commission. Then the commission makes no deliberations. And so, the pope only has them to listen to because our voice cannot reach him. How can you force the Pope to read the minutes—they are thick. Three days of talking.

So one day I complained to the Pope. I said, “You made me a Cardinal. You said that I should help you with the Church in China. But what can I do? Nothing! Nothing. They have the power. And you don’t say anything. You don’t help me, how can I help you?”

I was very rude to the Holy Father, but he was too good, too kind. And so both the letter and especially the commission—the commission did not only defend the wrong translation but defended the wrong interpretation. The wrong interpretation went around the whole of China. It’s terrible.

But what is happening now? Francis came. Now I’m sorry to say that I think you can agree that he has low respect for his predecessors. He is shutting down everything done by John Paul II and by Pope Benedict. And obviously they always give lip service, they always say “In the continuity…” but that’s [Slaps table] an insult. An insult. Not in the continuity.

In the year 2010, Parolin and Dias, they agreed with the Chinese part on a draft. And so everybody started saying, “Oh, now an agreement is coming, it’s coming, it’s coming” All of a sudden, no more voice.

I have no evidence, but I believe that it was Pope Benedict who said no. He could not sign that agreement. And I think the one agreement signed now must be exactly that one, which Pope Benedict refused to sign.

NH: You haven’t seen this agreement, they haven’t shown this to you?

CZ: No! I ask you, if that’s fair.

I am one of the two living Chinese Cardinals and I cannot have a view of that agreement, and I’ve been three times to Rome.

NH: How was your relationship with Francis at the beginning of his Pontificate? Was it always strained?

CZ: With Francis, personally wonderful relations. Even now. At the beginning of July this year, I had supper with the Pope. But he doesn’t answer my letters. And everything that happened is against what I suggested.

There are three things. A secret agreement, being so secret you can’t say anything. We don’t know what is in it. Then the legitimization of the seven excommunicated bishops. That’s incredible, simply incredible. But even more incredible is the last act: the killing of the underground.

Now they finished their job. On the 28th of June, a document came out from the Holy See—the Holy See. Never had a document come out from the Holy See, always from a particular department, with the two signatures. This had no department specified and no signature—from the Holy See. Incredible. Incredible. Somebody doesn’t dare to take responsibility.

I went to Rome again. For the third time. I went in January last year, October last year, and then June this year. I sent a letter to the papal residence, saying, “Holy Father, I am here in Rome. I would like to know who drafted that document. The so-called pastoral orientation. And I want to discuss with him on that document in your presence. I am here in Rome for four days, you can call me anytime, day or night.”

After one day, nothing. So I sent another note, but this time with all of my objections to the document. I said, “I’m still here waiting.” So after another day, somebody came to say, “The Holy Father said, whatever you have to say, say to the Secretary of State, Cardinal Parolin.” I was furious.

I said “No! I would never waste time with that fellow,” I said. A real waste of time, because I would never convince him, he would never convince me. I would like the Holy Father to be present. But since that seems impossible, okay, I’ll go home empty-handed.

The last day I went around to pray in some Basilica and to visit some friends, also Cardinal Tomko- -95 now, eh?

NH: Still in good health?

CZ: [Nods.] But seemingly not very active anymore. I came back to the house there at five o’clock. They said, “Oh, the Holy Father invites you to supper together with Parolin.”

I went there to the supper. Very simple, the three of us. I thought supper is not a time to quarrel, so I had to be kind during supper. So I talked all about Hong Kong, and Parolin didn’t say a word. So at the end, I said, “Holy Father, what about my objections to that document?” He said, “Oh, oh, I’m going to look into the matter.” He saw me off at the door.

And then, I did not come back empty-handed. I have a clear impression that Parolin is manipulating the Holy Father.

NH: What does Parolin want?

CZ: Oh, nobody can be sure, because it’s a real mystery how a man of the Church , given all his knowledge of China, of the Communists, could do such a thing as he’s doing now? The only explanation is not faith. It’s a diplomatic success. Vainglory.

Photo credit: VOA/Public Domain

Photo credit: VOA/Public Domain

Now this last act is simply incredible. The document says, “To minister openly, you need to register with the government.” And then you have to sign. To sign something in which it says that you have to support the independent church. That’s not good, actually we are still discussing on that problem. And so the government is not good because they are anticipating. But anyway, “You sign.”

The document contains something against our orthodoxy and they are encouraged to sign. You cannot cheat yourself. You cannot cheat the Communists. You are cheating the whole world. You are cheating the faithful. To sign the document is not to sign a declaration. When you sign, you accept to be a member of that church under the leadership of the communist party. So terrible, terrible.

Recently I learned that the Holy Father, on a flight back from (I don’t remember where) said, “Sure, I don’t want to see a schism. But I’m not afraid of a schism.” And I’m going to tell him “you are encouraging a schism. You are legitimizing the schismatic church in China.” Incredible.

NH: What do you think is the logic of Chinese Communist Party, their reasoning for wanting to control the Catholic church, to run the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association (CPCA)?

CZ: Sure, it’s their system. They need to control everything. Since they know that they cannot destroy, they want to control. Obviously. All the churches. They want to destroy from within.

NH: Do you think there’s a fundamental contradiction between having an open Catholic faith in China and having a China controlled by the Communist Party. Can you have a Catholic church in China with the Communist Party?

CZ: They are so afraid of what happened in Poland. They said it openly. When the Pope made me a cardinal, Mr. Liu Bainian [Editor’s note: the vice-chairman of the CPCA] “If all the Bishops in China are like Cardinal Zen, then we are going to become like Poland.” They are afraid of that.

They cannot tolerate it. You know, the problem with Buddhists in Tibet, and the Muslims in Xinjiang is even more complicated because it’s connected with race. And our problem is that we are a universal Church. So there’s no hope, no hope at all. No hope.